Scope And Purpose Of This Post

|

| Visual metaphor for DCA's inconsistency |

Dollar cost averaging (DCA) is a strategy deliberately delaying investing money. I will argue that DCA is an ill-founded and logically inconsistent way to manage risk. The superior way to manage risk is a well-chosen asset allocation.

I'm going to take some time to define my terms, because people use the term DCA in different ways. I'm not arguing against all of the different flavors of DCA, just a particular flavor.

I'll point to some existing great work on how DCA has been disappointing historically, but the heart of the post is explaining on a conceptual basis why DCA is disappointing and not a coherent approach to investing. Proper asset allocation is the superior and coherent way to manage risk.

Terminology

S/B notation: for this post, "75s/25b" is shorthand for "75% stocks, 25% bonds". It can be shortened to "100s" for "100% stocks" and it can be extended to "70s/20b/10c" to indicate 10% cash as well.Asset Allocation: the proportions of stocks, bonds, real estate, cash, gold, etc, that you own. For instance, you might have a desired asset allocation of 75s/25b, or a more aggressive 100s/0b. Your desired asset allocation should reflect the risk-and-return profile that is appropriate for you.

Cash: in investing/savings contexts, this isn't just physical dollar bills, but also very short-term interest-bearing assets, like money in a savings account, money market fund, or even 1-month treasury bills. These are very "safe" assets in being very unlikely to lose nominal value.

Lump Sum Investing (LSI): if you receive a sum of money, you immediately invest it in accordance with your desired asset allocation. For instance, you inherit $100K dollars and you immediately invest it in stocks and bonds in accordance with your desired asset allocation of 75s/25b. The core goal of LSI is to invest earlier rather than later to get more growth out of your money and to keep your asset allocation in line with your desired risk-and-return profile.

When people say "dollar cost averaging" (DCA), they usually mean one of two things:

- DCA1: If you receive a large sum of money, you don't do Lump Sum Investing (LSI) where you invest it all at once. Instead, you initially keep the money as cash and invest it gradually over time, perhaps over a period of years. The core goal of DCA1 is to invest across time to buy in at different price levels (thus the name) and to avoid investing all of your money at an unfortunate time (like a stock market peak). This is "DCA as opposed to LSI".

- DCA2: Continuously saving and investing (like every time you get a paycheck) over the course of years. Just keep investing, don't try to time the market and pull out of equities before a predicted stock market crash. The core goal of DCA2 is to invest your money as you earn it and to stick with your plan even when things looks scary. This is "DCA as opposed to market timing".

- How To Invest a Lump Sum, where he argues for LSI and against DCA1: "What if the market crashes right after you invest? Wouldn’t it be better to average-in over time (i.e. dollar-cost averaging/DCA) to smooth out any unlucky timing on your part? Statistically, the answer is no."

- Even God Couldn’t Beat Dollar-Cost Averaging, where he argues for DCA2 and against market timing: "You have 2 investment strategies to choose from ... Dollar-cost averaging ... Buy the Dip".

DCA1 is what I will argue against. I approve of DCA2, which is really just the buy-and-hold (BAH) part of the Boglehead passive investing approach. The next section will spend some more time distinguishing DCA1 vs DCA2 so that we don't think about "dollar cost averaging" in a confused manner.

Buy-And-Hold (BAH) Is Not Dollar Cost Averaging (DCA1)

I am purely on the side of LSI, and against DCA1. You might be tempted to say I do DCA1 because my investments in the stock market have been spread out over time, but you would be super-duper embarrassingly wrong because really I am doing pure LSI.Everytime I get money, I immediately invest it in a way compatible with my desired asset allocation, regardless of whether the money is $100 or $100K. I don't try to spread out my investing over time, it's just that my access to new money is spread out over time (my paychecks). A LSI investor with a regular paycheck is not a DCA1 investor even if the two investors both invest part of every paycheck.

This appearance of similarity is why people like to to say that BAH/DCA2 is "dollar cost averaging", but we can see that BAH/DCA2 people are not deliberately trying to do any dollar cost averaging; they're lump-summing as much as they can.

Against DCA1, The Historical/Empirical Approach

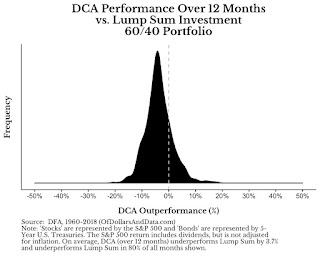

This How To Invest A Lump Sum post from Of Dollars And Data does a good job of empirically demonstrating that LSI outperforms DCA1 frequently and by significant amounts and when DCA1 outperforms LSI, it's usually by a smaller amount. There are many useful visualizations in the post, such as this one concerning 12-month timespans:And here's a really doozy for 24-month timespans, visualized differently:

Look at how rarely and by such small margins that DCA1 beats LSI over a 24 month span.

I think the Of Dollars And Data post does a really good job showing that DCA1 has historically sacrificed a lot of return to get a small reduction in risk. The better way for an investor to reduce risk is to make changes to their asset allocation.

Against DCA1, The Conceptual Approach

|

| Logical Lassie, The LSI Lady |

For the following discussion, let's imagine that Lassie is a LSI investor and Derek is a DCA1 investor. They are 20 years old, and have no prior savings, but they both inherited $100K on 1990/Jan/01. They both feel 100s (100% stocks) is appropriate for their young age and risk-tolerant mindset. Lassie immediately buys stocks in accordance with her desired asset allocation. Derek initially keeps his inheritance in cash and over the course of two years, shifts into 100s, each month converting ~$4.2K of cash into stocks.

DCA1, Conceptually A Loser In The Average Case

It should be expected that Lassie beats Derek in the average case: at every point in the first two years, Derek has his portfolio more in cash, and less in stocks than Lassie would. On average, cash has lower returns than stocks (and bonds). The historical stuff in the previous section is in agreement with this. You might read articles that praise DCA1 for delaying stock purchases so you can make some purchases at the low point in price fluctuations, but since the stock market trends upward, most of the time you're buying at a higher price than the initial lump sum price. | |||

| Disappointed Derek, The DCA Dude |

DCA1, Conceptually Inconsistent

Did it seem weird to you Lassie and Derek felt 100s was appropriate for themselves...but Derek spent much of 1990-1992 with a portfolio significantly different than 100s? Why was 100s appropriate for 1992 but not 1990? If an alternate Derek had received the $100K in 1988, then alternate Derek would be 100s at the start of 1990, very different from original Derek's 100% cash.Or, imagine Derek 's older brother Daniel. Daniel had $100K, deliberately all in stocks, and then inherited $100K on 1990/Jan/01 as well. If Daniel goes with DCA1, that means Daniel should immediately change from liking 100s to wanting 50s/50c, but also to gradually get back to 100s. I'm getting whiplash.

DCA1 is a rejection of asset allocation to control your risk-and-return profile. DCA1 leads Derek and Daniel to have asset allocations very different from what they previously decided made sense for them. If 100s (or 75s/25b) is a portfolio that makes sense for them, then they should be at that asset allocation no matter how long ago they got the money.

Derek could defend his decision to do DCA1 by saying that he'd hate to be fully at the mercy of stock market prices at a single point in time (1990/Jan/01) like Lassie is. He'd be more comfortable having his life savings depend on stock market prices across a span of time. The counterpoint is that on 1992/Jan/01, Lassie and Derek will both be fully at the mercy of stock market prices of that single point in time. Why is it okay to be fully at the mercy of the stock market in 1992 but not 1990?

If Derek chooses to do DCA1 because of fears of stock market volatility, then he should make a coherent decision to make his asset allocation more conservative. He shouldn't be 100% in stocks or 0% in stocks just because of how long ago his rich uncle died.

None of these points require young, aggressive investors with desired asset allocations of 100s. The same arguments can be made around basically any desired asset allocation.

This is a very interesting read, thank you. Especially the statistics give me a good insight into the facts behind it. However, the conceptual parts don't entirely work for me. If stock would go from 0.01 to 1 million one on the other day (unpredictably), for the rest of time, but then with an average of 10% increase yearly, it would be a lot more risky to LSI and DCA would make more sense (but maybe in a shorter timeframe then over 2 years). Second point: You counter the point of not being at the mercy of the stock market, but willing to be at the mercy in 1992. The risk there is the fluctuation of the buying price, so it only matters at time of conversion from cash to stocks. When you are all in stocks, you can rely on the averaging of the long term and the "mercy" is not applicable because as long as you don't cash out (which is the case for these two people) you depend on the average, not the fluctuations.

ReplyDelete>If stock would go from 0.01 to 1 million one on the other day (unpredictably), for the rest of time, but then with an average of 10% increase yearly, it would be a lot more risky to LSI and DCA would make more sense

DeleteCould you restate the behavior of the stock? It goes up to a million in a day then annually +10% on average after that? Or, on some days it goes up/down a lot (1e8 fold) and some days it goes up at what would be an annual +10%?

>The risk there is the fluctuation of the buying price, so it only matters at time of conversion from cash to stocks.

And stocks tend to fluctuate up over time, so DCA1 would tend to buy at higher prices than LSI. Asset allocation is the superior risk management tool.